By Gayatri Sahaay

Pune, India. 07 June 2021. From advocating for independence to attempting to bring lasting peace, the United Nations has had a long history of involvement in Africa. Following the establishment of the UN and adoption of the Charter in 1945, Article 73 calling for “self-government” and “the progressive development of free political institutions” gave African people renewed hope to be the masters of their own future. The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) also provided them with a forum in which their political aspirations could find voice and support.

1960 was a crucial year for both Africa and the UN, with fifteen African countries achieving independence and sixteen new African states admitted into the UN. 1960 also witnessed the landmark “Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples” which advocated the need for a speedy and unconditional end to colonialism.

The post-colonial era, however, proved to be a challenging time. Newly independent states lacked strong democratic institutions, and became the theatre of civil conflicts whereby rival ethnic, religious, or other groups fought for access to power and resources. As a result, African issues dominated the agenda of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) in the early 60’s, with issues concerning The Congo Question, the situation in the Union of South Africa, and Apartheid.

After Nigeria gained its independence from Britain in 1960, the country became divided into ethnically defined regions. Violence broke out as the nation’s military took power, leading to countless civilian deaths. Although Nigeria has just acquired membership, discussions regarding the decolonization process and the subsequent Biafran War were absent in both the UNSC and the UNGA even in the following years. The UNSC has also long been criticized for not establishing an international criminal tribunal in Nigeria after the war, as it had done in other conflict-ridden situations.

Following this, in 1991, a coup ousted dictator Mohammed Siad Barre, the President of Somalia. This shifting balance of power sparked a twenty civil war that killed as many as one million Somalis via violence, famine or disease. The country became divided into two opposing parties, and this made it difficult to achieve control of the conflicting factions, because no one ruling entity was recognized by all Somalis. The UN became heavily involved in the conflict from 1992 to 1995, sending military forces and humanitarian aid to the country. The civil war’s large death toll could possibly have been avoided with earlier humanitarian action according to a 1999 report commissioned by former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan.

Next, between April and July of 1994, the Hutus – a Rwandan ethnic group – murdered the Rwandan President Juvenal Habyarimana. This triggered the systematic genocide of approximately 800,000 Tutsis, the ethnic minority of Rwanda’s population. As a result of the conflict, the UN established a military presence in Rwanda but did not have the authorization to take action. The massacre ended when the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RFP) invaded the capital and defeated the Hutus.

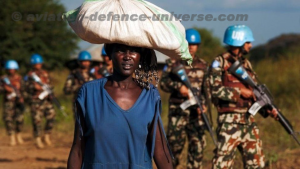

Post this, in 1987, The Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) began the longest-running rebel upheaval in Uganda, resulting in the displacement of nearly two million people and the deaths of thousands. The regime has become notorious for abducting and forcibly recruiting children to serve as soldiers and sex slaves. The recognition that the LRA is “involved in planning, directing, or committing acts that violate international human rights law” was first recognised by the UN in Resolution 2262 in 2016. The battle to end the LRA’s terror has been ongoing for two decades. The UN peacekeeping mission has taken a robust military approach against the LRA and other armed groups in recent years. Its “blue helmets” work with the Congolese armed forces in leading military operations and the also facilitate the provision of humanitarian assistance in areas affected by the LRA.

Moving on, in 1988, a two-year war between neighboring countries Eritrea and Ethiopia was triggered over a border dispute and claimed approximately 80,000 lives. A lack of dialogue and a climate of fear between the countries led to economic tension, political unrest and a decrease of overall growth within the area. The dispute saw an end in 2000, after the two countries negotiated a cease-fire agreement called the “Algiers Peace Treaty”. In July 2000, UNSC Resolution 1312 established a mission to monitor a ceasefire in the border war. The mission was formally abandoned in July 2008 after experiencing serious difficulties in sustaining its troops due to fuel stoppages.

These examples of conflict in Africa’s history helped shape its past, and the effects of UN efforts or lack thereof are being felt long into the future.

As of today, the UN has deployed seven peacekeeping missions in Africa. One of them being the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA). Its purpose is to support the political process and help stabilize Mali. It was established by UNSC Resolution 2100 in 2013 to support the authorities of Mali in implementation of the transitional roadmap. By unanimously adopting Resolution 2164 in 2014, the Council further decided that the Mission should focus on ensuring security of civilians, supporting political dialogue, and assisting the re-establishment of state authority. This mission has deployed 18311 personnel to Mali.

Another important mission is the United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO). MONUSCO took over from an earlier UN peacekeeping operation in 2010, and is in accordance with UNSC Resolution 1925 to reflect the new phase that Congo is in. The new mission is authorized to use all necessary means to carry out the protection of civilians under imminent threat of physical violence and to support the Government of the DRC in its peace consolidation efforts.

Another key peacekeeping mission is the United Nations Mission in the Republic of South Sudan (UNMISS). When South Sudan became the newest country in the world in July 2011, it was the result of the culmination of a six-year peace process which began with the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement. In adopting Resolution 1996 in 2011, the UNSC determined that the situation faced by South Sudan continued to constitute a threat to international peace and established UNMISS to help create conditions optimal for development. Following the crisis which broke out in December 2013, the UNSC reinforced UNMISS and reprioritized its mandate towards human rights monitoring by Resolution 2155.

Finally, the United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone (UNAMSIL) is one of the UN’s biggest success stories. The perseverance in persuading Sierra Leoneans to pursue a negotiated end to the war was noteworthy. One of the most remarkable aspects of the peace process was the disarmament of Revolutionary United Front and Civil Defence Force combatants. UNAMSIL also assisted the parliamentary elections in May 2002, only four months after combatants had handed over their weapons.

Through the deployment of various peacekeeping operations, the UN has sought to assist the transition to peace, facilitate dialogue between confliction parties, and help strengthen democratic institutions. These missions have promoted human rights, social cohesion, and reconciliation at both the national and local level.

However, the porous borders of most African countries, coupled with generally weak institutions and political instability, have led to the sustenance of illicit activities such as arms smuggling and narcotics trade. In order to counter these, the UNSC has oftentimes imposed embargoes on countries in the region and established monitoring mechanisms like The Group of Experts in Côte d’Ivoire.

In addition, one must not forget that large swathes of West Africa remain significantly underdeveloped and affected by recurrent humanitarian crises caused by food scarcity, epidemics, and drought. The UN has tried to address these as well. Firstly, in September 2014, the international community established the first ever emergency health mission the UN Mission for Ebola Emergency Response. The mission closed on 31 July 2015, having achieved its core objective of scaling up the response on the ground.

Secondly, climate change also poses a significant threat to economic, social and environmental development in Africa. The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) works in the region to focus on supporting countries in implementing their climate action commitments. The EU-UNEP Africa Low Emissions Development Project has worked with 7 countries to unlock both environmental benefits and socioeconomic dividends simultaneously.

Thirdly, corruption remains the most daunting challenge to good governance, sustainable economic growth and development in Africa. While a United Nations Convention Against Corruption does exist, addressing the problem of corruption in a strategic way is of paramount importance as a development priority for Africa. Various scholars have expressed the need for an international treaty to establish an African commission against corruption, involving UN inspectors to investigate and prosecute corruption.

And lastly, in eleven African countries, women hold close to one-third of the seats in parliaments. With 61 percent, Rwanda has the highest proportion of women parliamentarians in the world. Through regional offices in Dakar and Nairobi, UN Women implements programmes to promote women’s participation in decision-making by supporting leadership development.

Despite all UN efforts targeting Africa, a lot remains to be done, which calls for additional measures that could enable the UN to be more effective in the region.

In several parts of Africa, the UNSC, with its five permanent members, has contributed to a perception of the UN as promoting the interests of a few superpowers and, more specifically, the former colonial powers. Large sections of the population in African countries feel somewhat detached from the UN. A few armed groups, of which Boko Haram is a glaring example, display an increasingly defiant attitude vis-à-vis the UN. A Security Council in which African countries have a more entrenched role, if not a permanent seat, may help bridge the gap between the UN and the people whom it is called upon to assist.

The defiant attitude of some groups towards the UN may also be due to the organization being perceived as generally weak. UN peacekeepers are often seen as passive, unable, or unwilling to use force in response to attacks. In this context, the establishment of a direct intervention brigade in the United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO) is a welcome development, which may help change this perception. If possible, this measure could be applied in other places, such as Mali, where the UN has recently become a target of attacks.

Alternatively, the UN should further enhance and institutionalize its co-operation with regional organizations, such as ECOWAS and the African Union, helping them to increasingly take the lead and responsibilities in resolving conflicts in Africa.

Moreover, it would seem important that the political commitment of member states to address a crisis is accompanied by the required financial commitment. Today, the organization is asked to achieve more results with less resources. Member states want the peacekeeping budget to stay the same even as new peacekeeping operations are established, as in Mali and the Central African Republic. This is not a realistic approach, if the UNSC chooses to deploy a peacekeeping operation, a more effective mechanism needs to be in place to ensure that funding is readily available. If this is not achieved, as new peacekeeping operations are established, there emerges an urgency to downsize or close other mission (like in Côte d’Ivoire, Haiti, Liberia), even when the situation in those countries has not completely stabilized. This risks a slide back into conflict following the mission’s departure.

As a matter of fact, the UN must make greater efforts at preventing crises before they erupt. While great progress has been made over the past decade to strengthen the preventive diplomacy tools of the UN, it still remains difficult for it to find political space for early engagement due to concerns over interference in internal affairs. The UN should consider the possibility of setting up a robust early warning mechanism that must include an improved intelligence system.While peacekeeping is a challenging ordeal, the UN has been successful in the past, and can do so again by incorporating certain structural changes and acquiring better financial backing to see to the end of conflict in Africa.