- “India does not seek conflict, but must be fully prepared for it—militarily, diplomatically, technologically”

- “India’s destiny will be shaped not by how we fight wars—but how we prevent them”

- “The 21st century will not be defined by who fires the first shot, but by who can prevent it”

By Sangeeta Saxena

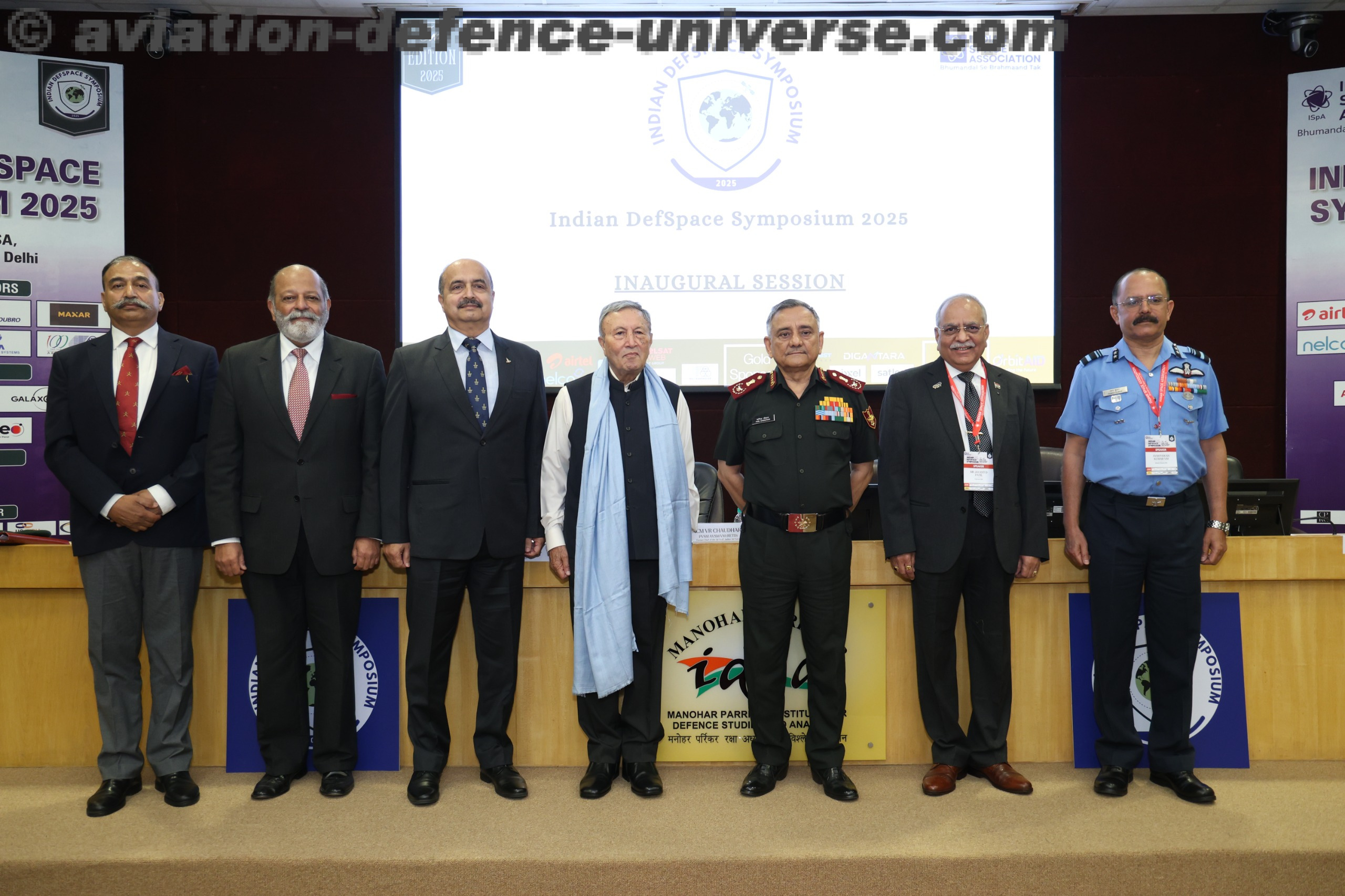

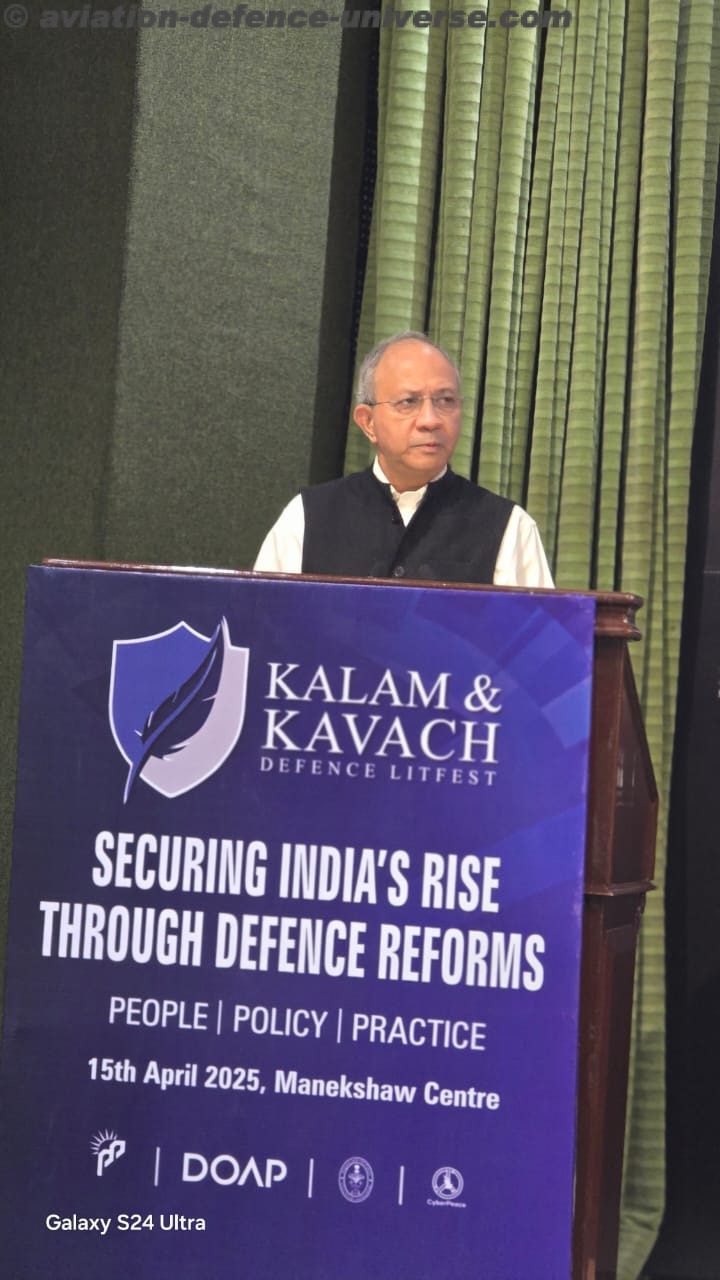

New Delhi. 17 April 2025. At the Manekshaw Centre in Delhi, where some of the nation’s sharpest military and strategic minds had gathered for the Kalam & Kavach Military Literature Festival, former Deputy National Security Advisor and diplomat Ambassador Pankaj Saran who heads the NatStrat a Centre for Research on Strategic and Security Issues, delivered a compelling address that dissected India’s long and winding journey of defence reforms. With piercing insight and candid reflections, Saran called for a collective awakening, urging that reform must no longer be a reactive compulsion but a proactive and strategic choice if India is to emerge as a true global power.

“The 21st century will not be defined by who fires the first shot, but by who can prevent it,” these words, spoken by Ambassador Saran, set the tone for an incisive and timely brainstorming at the Kalam & Kavach Military Literature Festival 2025 on defence reforms. With decades of experience in international diplomacy and strategic affairs, Ambassador Saran brought rare insight into India’s unique geopolitical position—flanked by an assertive China and a fragile neighbourhood with not-so-friendly nation like Pakistan, yet rising as a confident voice in global forums.

Ambassador Saran opened his keynote with a dose of realism laced with humour, welcoming the Ministry of Defence’s recent declaration of the “Year of Defence Reforms,” while wryly wishing every year could be declared the year of reforms. But beneath the levity was a serious proposition: the engine of reform must run continuously, not episodically. He framed reform as an essential instrument of statecraft, one that demands clarity of purpose, timing, and intent—not just crisis-induced compulsion.

Ambassador Saran opened his keynote with a dose of realism laced with humour, welcoming the Ministry of Defence’s recent declaration of the “Year of Defence Reforms,” while wryly wishing every year could be declared the year of reforms. But beneath the levity was a serious proposition: the engine of reform must run continuously, not episodically. He framed reform as an essential instrument of statecraft, one that demands clarity of purpose, timing, and intent—not just crisis-induced compulsion.

Citing India’s landmark economic liberalisation in 1991 as a reform born of desperation, Saran contrasted it with more deliberate changes like the restructuring of the power and digital sectors, and the recent opening up of space. These examples, he said, highlight two critical truths: first, that success often accelerates reform, emboldening decision-makers; and second, that reform is rarely linear—it stumbles, stalls, and must be allowed to fail and adapt.

“I think the question of defence reforms is not a Ministry of Defence issue or an Armed Forces, IDS or CDS issue. It is all you expect. They say about China, it is too important to be left to the China watchers. I think similarly, defence reforms is too important to be left to the uniformed or the Ministry of Defence bureaucracy. It is a national effort. So, for example, if you have something like the offsets policy, the offsets policy is made in the Ministry of Industries. And there is very little discussion between the Defence Ministry and the Ministry of Industry and the Ministry of Finance, let us say, on the FDI protocol or the policy. So, defence reform, I think, in terms of its strategic significance, goes beyond just the narrow kind of framework of the Defence Ministry.”

He outlined India’s approach as being one rooted in civilisational confidence, but reinforced by strategic clarity. “India does not seek conflict,” he said, “but must be fully prepared for it—militarily, diplomatically, technologically.” Central to his address was the notion that deterrence is dynamic. It must adapt to the changing nature of threats—from traditional warfare to cyber intrusions, drone swarms, space-based surveillance and AI-driven battlefields. “Modern warfare is no longer about tanks and trenches alone—it’s about narratives, technologies, and control of the information space,” he stressed. “This is where India must prepare—to lead, not follow.”

Ambassador Saran identified three crucial pillars to securing India’s future. The first one is military modernisation which means not just buying weapons but building an ecosystem of innovation, manufacturing and skill development in India. The second is technological sovereignty which indicated investing in dual-use technologies, especially in AI, quantum computing and space surveillance. The third is global partnerships with Indian priorities which is engaging the world on India’s terms—aligned with our interests, values, and vision of Viksit Bharat.

On the role of diplomacy, he reiterated that military power without strategic direction can be dangerous. “Diplomacy is our first line of defence. But it works best when backed by credible military and economic heft.” As the audience at the Military Literature Festival soaked in his words, one theme resonated deeply—India must now write its own grand strategy, blending hard power with the soft power of its civilisational legacy.

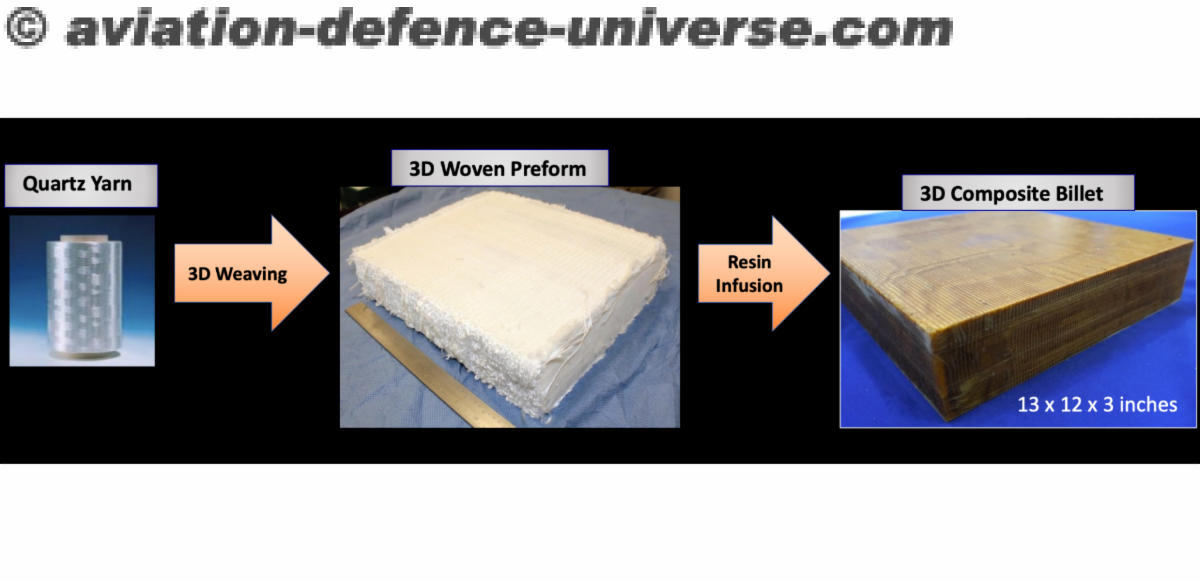

The Ambassador made a strong pitch for defence manufacturing to be seen as a pillar of national strength, on par with economic and technological progress. “No country becomes a global power on the back of services alone,” he stated, adding that a nation that still relies on imports for the bulk of its defence needs cannot call itself secure or sovereign. His view was unambiguous: India must move from being the world’s second-largest arms importer to a top-tier manufacturer and exporter of defence systems.

“If you anecdotally do a survey of countries across the world, it is easy to see that there are probably not more than 10 odd nations in the world who are, who could be considered as defence manufacturers or countries that produce defence equipment on scale. And we have to ask ourselves why is it that out of 193 countries, we only have 10 or 15 who are actually defence manufacturers. And that there is a strong correlation between these 10 and 15 and their role as major or influential global powers. So, I think there is a almost indisputable case to be made that if you want to be a major power, a credible power and a strong power, you have to have a strong defence manufacturing base.”

Importantly, Saran challenged the notion that reform is solely the Ministry of Defence’s mandate. “Defence reform is a national effort,” he asserted, highlighting how disconnected policies between ministries—from defence to industry to finance—create friction and dilute outcomes. The offsets policy, FDI norms, and regulation of private industry must be harmonised, he said, under a unified strategic vision.

But for all the hurdles, Saran also spotlighted success stories—the corporatisation of the Ordnance Factory Board, pension reforms, and the launch of the Agnipath scheme, among others. He acknowledged that not all were perfect or universally accepted, but they were reform milestones nonetheless. What mattered most, he argued, was the willingness to self-correct, iterate, and evolve. “The real test is whether we stick with the decision and improve it—or endlessly debate it into irrelevance.”

Closing on a note of cautious optimism, Saran observed that the psychological barriers to reform—those “holy cows” around defence, space, and nuclear policy—were finally being breached. The time for lip service is over, he said, and what remains is to treat industry as a partner, not a vendor; to make innovation a societal mission, not a government chore; and to build a truly national consensus around the urgency of reform. “If we can do what we’ve done in the last few years,” he concluded, “surely we can do more, at scale, in the years ahead.

“India’s destiny will be shaped not just by how we fight wars—but by how we prevent them, and how we build enduring peace through strength, ” was his parting shot resonating the Ashoka Hall of Manekshaw Centre with thunderous applause.