By Commodore Anil Jai Singh, IN (Retd)

New Delhi. 23 June 2021. Recent reports that the Government is likely to give its nod very soon for the construction of six nuclear attack submarines (SSN) is very heartening and could not have come a moment too soon. This follows the approval that had been accorded by the CCS in February 2015 for a preliminary design study for the indigenous SSN programme. It is perhaps the successful completion of that phase which has led to this requirement to take the programme further. It is also understood that the Indian Navy has requested that the 30 Year Plan for indigenous submarine construction which had been approved by the CCS in 1999 for the construction of 24 conventional diesel-electric submarines be amended to include six SSNs and reduce the conventional numbers to 18.

The origins of India’s SSN aspirations are not recent. The Indian navy’s tryst with nuclear power began in January 1988 with the commissioning of INS Chakra, a Charlie-I class SSN leased from the erstwhile Soviet Union for three years with the intention of gaining expertise in the operation and maintenance of these extremely complex platforms and developing a knowledge base for the future. A long hiatus followed with the focus shifting to the SSBN (nuclear powered ballistic missile submarine) programme. Since ‘No First Use’ and ‘minimum credible deterrence’ became the cornerstones of India’s nuclear doctrine, a credible second strike capability became an imperative for which a SSBN is the ideal platform. India’s SSBN capability continues to develop with the commissioning of the Arihant in 2017, its first successful deterrence patrol in 2018, the second SSBN Arighat undergoing advanced sea trials and at least two more SSBNs at various stages of construction.

The lease of an Akula-2 class SSN from Russia for a period of 10 years in 2012 perhaps signalled the intent to continue progressing the SSN development. Valuable expertise has been gained in nuclear submarine design, construction, operation and maintenance through the indigenous SSBN programme and the leased SSN which has recently departed for its return voyage to Russia on completion of the lease. It is understood that a USD 3.5 Bn contract has also been concluded for the lease of another Akula-2 class SSN for ten years commencing in 2025.

When the 30 Year plan had been approved in 1999, it was restricted to conventional submarine construction. However, the rapidly evolving geopolitical dynamics in the region, the emerging maritime security scenario and India’s own national interests have highlighted the need for India to re-assess its maritime capability. If India has to retain is maritime primacy in the Indian Ocean in the future it has to be able to has to be able to project power and bring adequate force to bear to protect India’s interests wherever and whenever it may be called upon to do so.

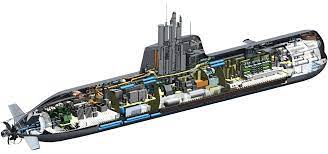

SSNs are the ideal blue water platforms and perfectly complement an aircraft carrier-centric blue water force architecture. They are agile, flexible, can do high speeds underwater for indefinite periods, have unlimited endurance and pack a lethal punch with an armament of smart heavyweight torpedoes and tube- launched cruise missiles capable of precision strike on targets at sea as well as deep inland from stand-off ranges at sea which make them fairly invulnerable to a counter attack. They can operate in company or independently and have the ability to the operational maritime battlespace to advantage. A force level of six SSNs will give great boost to India’s blue water naval capability to shape the outcomes in the Indian Ocean. These submarines will be able to effectively blunt the PLA Navy’s intent to dominate the Indian Ocean and severely limit its attempts to shape the maritime order in the region with its naval muscle.

In the 55 years since the Indian Navy’s submarine arm came into being, conventional submarines have been the principal instruments of India’s undersea warfare capability in the littorals as well as in the open ocean. The SSNs will add a new dimension to India’s ooen ocean submarine deployment which will also enhance the SSK availability in the littoral waters of the Arabian Sea, the Bay of Bengal, and the approaches to the Eastern Indian Ocean for which they are better suited.

Now that India is more or less committed to a SSN capability to address its blue water concerns, what impact will this have on the choice of design for the P75(I) programme ? How best can the SSN and the SSK capability complement each other in optimising the numbers and the capability across the full spectrum of maritime conflict to protect India’s security interests ?

The P75(I) programme for the indigenous construction of six conventional diesel electric submarines (as part of the 30 year plan) through the Strategic Partnership model in collaboration with a foreign submarine builder is also being progressed by the Government. Approval of the Defence Acquisition Council (DAC) headed by the Defence Minister to issue the Request for Proposal (RfP) to the two shortlisted Strategic partners, the state owned Mazagon Docks Ltd Mumbai and the private sector engineering conglomerate, Larsen and Toubro was accorded on 04 June 2021. This long overdue step (the first AoN had been issued over a decade ago in 2010) has re-focussed attention on the urgent need to address India’s depleting and ageing submarine force levels and the need therefore to progress this programme expeditiously. However, this is only the first step in a long and complex process.

Once these two shipyards receive the MoD’s RFP, they will, in turn develop a RFP and issue it to the following five foreign OEMs which have been shortlisted based on their submarine building track record and their current submarine designs – Thyssenkrupp Marine Systems Germany (Type 214, 218), Naval Group France (Scorpene), Navantia Spain (S80 Plus), Rubin Design Bureau (Amur) and Daewoo South Korea(KSS-III).

The five designs being offered, despite similarities in the capabilities they offer are quite distinct from each other in many respects, the most significant being their displacement. While three of these displace between 1700 and 1800 tonnes, the remaining two displace more than 3200 tonnes. The displacement of a submarine determines its size, stealth, power, armament, manoeuvrability etc. This is therefore an important consideration when deploying in a littoral environment where the depth of water is a constraint and the ability to avoid detection is a necessity.

The Indian Navy has from the every inception of its submarine arm operated submarines varying in displacement between 1500 and 2300 tonnes (the old Foxtrots displaced about 2000 tonnes, and of the present classes, the Russian Kilo class displaces about 2300 tonnes, the German Type 209 about 1500 tonnes and the newest, the Scorpene about 1700 tonnes) The wide difference between the Kilo and the Type 209, both of which were acquired in the 1980s was mainly because of the Soviet design philosophy of building double-hulled submarines whereas the Europeans preferred single-hulled for the most part. The heavier and bulkier equipment of the Soviet-era compared to the sophistication in the western origin equipment further contributed to a higher weight and displacement. This gap has now narrowed considerably. In the case of the P75(I), both the designs which displace over 3200 are essentially European and have been designed to be large for a reason.

South Korea and Spain have deliberately chosen a larger design based on their requirements in their area of operations. In the case of the South Korea, the KSS-III is meant to effectively counter the Chinese threat and North Korea’s nuclear rhetoric and aggressive intent. The KSS-III unlike its predecessors which were based on the German Type 209 and the Type 214 designs will be fitted with a vertical launch missile system capable of firing long range cruise missiles thus increasing the length and the displacement of the submarine.

In the case of the Spanish submarine, the decision to build a larger submarine capable of projecting power was taken at the highest levels of government and led to the rejection of the original S80 design which later came to be built by the French as the Scorpene class for export with Chile as its first customer. Subsequently the Spanish designed the S 80A Isaac Perla class which began construction more than a decade ago and encountered a major design flaw with a serious weight imbalance. This has been rectified in collaboration with Electric Boat, the USA’s premier submarine building yard and the revised design , now called the S 80Plus is about 10 metres longer and about 100 tonnes heavier than the original with no appreciable capability enhancement. Infact, Spain which had been highlighting its breakthrough ethanol based fuel cell AIP for over a decade is not installing on the first two submarines and will perhaps go to sea only on the third boat and not before 2025 at the earliest.

This raises some very serious questions about Indian approach to Project 75(I), one of which is the desired displacement of the submarine. Now that India is going ahead with the SSN programme which will address the blue water aspect of our undersea warfare capability, should the Project 75(I) submarine not be designed and optimised for operations in the shallower depths of the littorals?

The Arabian Sea, the Bay of Bengal and the eastern approaches to the Indian Ocean are going to be hotly contested waters within the next decade or so. The PLA Navy which already has a permanent presence in the Indian Ocean is set to grow its footprint in the coming years as the it continues to expand at a breath-taking pace with 20-25 major surface combatants and submarines getting commissioned year on year. As soon as it has the confidence and the capability to project power in the Indian Ocean, it will seek to dominate the Indian Ocean and challenge India’s primacy in these waters through its naval presence and its economic constructs like the Belt and Road Initiative with its strong strategic underpinnings.

In the Arabian Sea and the western Indian ocean, it already has a base in Djibouti, will soon control Gwadar which is just about 70 miles west of the strategic Straits of Hormuz through which 60% of India’s energy transits. Its recent overtures to Iran if successful will give it a stranglehold on the Hormuz and severely endanger India’s energy lifeline. It is wooing the islands located in India’s strategic maritime neighbourhood with economic and developmental inducements with no attempt to conceal its underlying motives. It is arming the Pakistan navy with eight submarines and four guided missile frigates to act as its proxy in the region. By the end of this decade, the Pakistan Navy will have a force level of 11 submarines, a figure totally disproportionate either to protect Pakistan’s limited coastline or its threat perception. Hence the likely deployment of these submarines needs no guesses. The north Arabian Sea, along the Makran coast and the waters between India and Pakistan are relatively shallow and therefore challenging for submarine operations. Hence, an optimal balance between size and capability is important for effective submarine deployment.

In the Bay of Bengal, China has already armed Bangladesh with two Ming class submarines and a frigate and is reportedly building a submarine base off Chittagong. President Xi Jinping has been deepening China’s economic engagement with Bangladesh and during his recent visit ‘warned’ that country to resist any initiatives in the region by extra regional powers with particular reference to the Quad. Bangladesh is emerging as a strategic factor in the region and China, with these two submarines has established a dependency for the maintenance, training and logistic support for these submarines which gives it crucial diplomatic and military leverage over that country. A permanent PLA Navy presence in the Bay of Bengal in the near future is therefore inevitable which will directly impact India’s interests in these waters.

India on its part has deepened its engagement with Myanmar to wean that country away from the Chinese stranglehold and has leased one of its Kilo class submarines to that country. However, the political uncertainty with the return of the military junta to power has caught India flat-footed. While the world reacted with strong criticism, India had to carefully calibrate its response. China, which already has a substantial presence in Myanmar will definitely exploit this uncertain political environment to enhance its influence in the Bay of Bengal and limit India’s options. An offensive deployment by medium sized SSKs in these restricted ocean spaces will be the most effective counter to this intent.

The southern Bay of Bengal is contiguous with the eastern Indian Ocean and the Andaman Sea. The location of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands and their proximity to the chokepoints controlling access to the Indian Ocean are a strategic advantage that India must leverage to advantage. An effective maritime domain awareness capability in this oceanic expanse complemented by a strong military presence in the islands and a networked undersea surveillance capability supported by an adequate SSK presence in the vicinity of the choke points and at the approaches to the Bay of Bengal would be able to effectively monitor the movement of PLA Navy ships and submarines and blunt any Chinese aggressive intent in the Indian Ocean at its approaches itself. A medium sized SSK with adequate range and endurance will be the ideal choice for effective monitoring of these waters.

The importance of submarines is going to increase exponentially as technology makes the surface of the sea increasingly transparent. Modern surveillance platforms and the advent of disruptive technologies in the surface, sub surface, air, space and cyber domains in a networked environment will greatly limit the ability of surface forces to operate undetected; further, their vulnerability to long range precision guided weapons will further inhibit their ability to seize the initiative. If India is indeed to defend its maritime frontiers and retain the initiative, it has to be able to effectively control the littoral waters and the strategic choke points giving access to the Indian Ocean. The submarine with its ability to deny the sea to the enemy and in favourable circumstances also exercise limited sea control in its immediate area of operations is the ideal platform.

It is therefore important that the submarine force levels are optimised for their envisaged role. In the specialised undersea environment where stealth and lethality are the key to success, a ‘One size fits all’ approach is inherently flawed.

Given the likely deployment areas in the littorals for SSKs in the future which will be complemented by a potent SSN blue water capability, should India be looking at platforms in excess of 3000 tonnes with their large displacement and consequent limitations of deployability in shallow waters with no appreciable capability advantage over submarines of almost half that displacement for Project 75(I) and eminently more suited to deployment in shallow waters? Size should denote additional capability. However, a cursory glance at the specifications of the existing designs indicate that the larger ones in contention in Project 75(I) do not offer any appreciable capability enhancement justifying the difference in displacement. In their own navies these were deliberately designed to be larger for an open ocean role that may actually be at odds with the Indian requirement of securing its littoral maritime space.

Project 75(I) is an extremely complex programme. There is still a lack of clarity on issues related to its progress under the SP model. This has been further aggravated by the number of contenders in the competitive bidding process. Widening the competition just for the sake of competition is likely to be counter-productive in the time taken to decide, the choice of platform and the enhanced risk with unproven technologies being offered to become compliant with the RfP. The capability of the designs on offer, their advantage and their limitations are known and understood by submarine professionals across the globe. The Indian Navy and its submarine arm is more than capable of defining its requirements and deciding the most optimum platform and capability it requires from amongst those available worldwide.

In this case, the decision is going to be influenced by the two contenders who will be negotiating with five different OEMs to offer a product based on a RfP which requires compliance on unproven technologies with the final selection hinging on who is the cheaper of the two. This approach is fraught with tremendous risk and ambiguity which could derail the entire programme or at the very least lead to time and cost overruns which nether the country nor the navy can afford. The effort should therefore be on mitigating the risks and addressing the ambiguities. Narrowing the displacement range based on the requirement may be a good place to start.

The author Commodore AJ Singh is an ex-submariner of the Indian Navy and a defence expert. He is the Vice President at Indian Maritime Foundation. The views in the article are solely the author’s. He can be contacted at editor.adu@gmail.com