By Cmde AJ Singh (Retd.)

New Delhi. 04 December 2019. A project conceived two decades ago and initiated one decade ago has finally shown some signs of progress in the labyrinth of the hallowed corridors of New Delhi’s majestic South Block which houses the offices of India’s Ministry of Defence.

Project 75 (India), a programme for the construction of six diesel-electric submarines in India in collaboration with a foreign submarine builder was part of the 30 Year Plan for indigenous submarine construction which was approved by the Cabinet Committee on Security (CCS) in 1999. It took 11 years for an ‘Acceptance of Necessity’(AoN) to be accorded in 2010. Lack of progress in deciding the way ahead led to another AoN being accorded in 2014 which also lapsed subsequently. Finally, in January 2019 the third AoN was accorded for the onstruction of six diesel-electric submarines through the Strategic Partnership (SP) model. The subsequent issue of two ‘Expression of Interest’ (EoI) documents – the first to five global submarine building OEMs and the second to Indian industrial entities who claim to have the potential to build submarines and are keen to participate in the programme as ‘Strategic Partners’ – has given rise to guarded optimism that this programme might finally make progress. The EoIs highlight the requirements set out by the MoD in terms of the platform, its equipment fit, willingness to transfer technology and ability to build the submarine in India. Based on their compliance to the EoI, the foreign OEMs and the Indian SPs will be shortlisted. For this, an Empowered MoD Committee, headed by the Indian Navy’s Controller of Warship Production and Acquisition(CWP&A) has been constituted to examine all aspects of this programme and to ensure its swift progress. The complexity of the programme will require extensive deliberations amongst all stakeholders because the IN/MoD is keen to get substantial value addition and adequate Transfer of Technology to be able to independently design and build the IN’s future conventional submarines. Once the potential Indian SPs are shortlisted, they will seek a collaboration with the foreign OEMs through a RfP process and thereafter choose their preferred partner based on their assessment. Finally, based on their bid, one SP will be selected.

Submarines constitute the cutting edge of a nation’s maritime offensive capability . In the context of the Indo-Pacific , he importance of a potent and contemporary submarine force cannot be over-emphasised. Regrettably, the Indian Navy today is beset with an ageing submarine arm and a delayed procurement programme which seems driven by considerations other than the primary objective of ensuring adequate and contemporary combat capability. It is therefore heartening to see positive movement in Project 75(I). However, the complexity and magnitude of this programme under the SP model will need a sustained and comprehensive effort by all stakeholders if this programme is indeed to see the light of day and establish India as a truly indigenous submarine builder. Particular attention will need to be paid to the following aspects :-

(a) Choice of the design of submarine and the selection of the foreign OEM

(b) Choice of the Indian Strategic partner

(c ) Extent of ToT demanded and capacity to absorb such depth of technology

(d) Making the optimum choice.

Choice of Submarine Design.

The selection of the submarine design will underpin the remainder of the programme. The global diesel-electric submarine market is dominated by a handful of submarine building OEMs. The EoI was sent to five of these – Naval Group, France , tkMS, Germany, Rubin, Russia, Navantia, Spain and Saab Kockums, Sweden). Each of these OEMs has an established submarine building legacy and all of them have committed themselves to adapting their design for India’s requirements. Since then Saab Kockums has withdrawn from the programme for a variety of reasons including liability issues and a late entrant is Daewoo (DSME), South Korea.

While two of these five have proven designs operating with foreign navies, a third has yet not been able to satisfactorily prove its design. The remaining two remain unproven at sea with one having experienced major design flaws and the other yet a design only on paper. Therefore, the Indian MoD must factor in not only the OEM’s legacy but its ability to offer a suitable platform in a defined time frame with minimum risk and its willingness to transfer technology with all of this coming at an affordable cost. India’s own experience with these OEMs in the past should also be an important consideration.

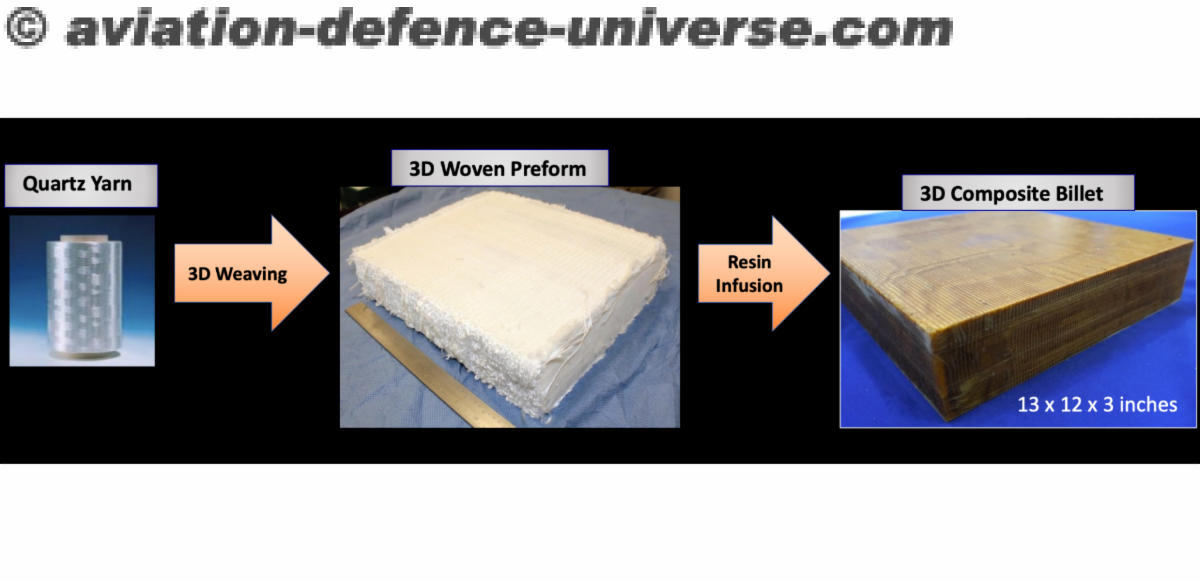

Amongst the major diesel-electric submarine operating navies including Pakistan, India is one of the few without Air Independent Propulsion (AIP) systems on board its submarines. An AIP system greatly enhances a submarine’s dived endurance and therefore eliminates to a large extent one of its major vulnerabilities of having to snorkel often for charging its batteries. In an increasingly transparent maritime battlespace, this vulnerability becomes even more acute. Regrettably, while AIP systems have been used on board submarines since 1989, even the new Indian Scorpene class are without these. Ironically, the Agosta 90B submarines, also built by Naval Group for Pakistan have a MESMA AIP system installed on board. India has indicated its preference for fuel cell technology for its AIP system for its future submarines and DRDO is also in the process of developing an indigenous fuel cell AIP. Of the five contenders listed above, only Germany’s tkMS has a fully proven fuel cell AIP system which is currently in use on many of its submarines operating with various navies worldwide. It is understood that Naval Group is also in the process of developing a fuel cell AIP system. Russia and Spain have yet to prove their fuel cell AIPs systems at sea. South Korea too claims to have successfully developed a fuel cell system. In the event of the DRDO system getting operational, this would probably become the default choice on IN submarines.

Choice of Strategic Partner.

Project 75(I) is the second programme being progressed under the Strategic Partnership Model, the first being the acquisition of 111 Light Utility Helicopters for the Indian Navy. Hence the success of these programmes is critical to establish the SP Model as the preferred mode for big-ticket acquisitions. While the SP model, as described in Chapter 7 of the Defence Procurement Procedure is restricted to private industry, an exception has been made in the case of this programme where the participation of Defence Public Sector Undertakings (DPSU) has been permitted. This is not unexpected because Mazagon Docks Ltd, a DPSU, is the only Indian shipyard with considerable experience in construction of diesel-electric submarines. The two indigenous German Type 209 submarines were built here in the early 1990s and the current Project 75 submarines are also being built here though there has been a long delay in the delivery of these submarines with considerable cost overruns and quality issues which cannot be ignored.

The MoD’s intention is to encourage maximum participation from private industry and has therefore given a fairly liberal criteria for companies to participate with the possible assumption that those who are not able to present a convincing case for their eligibility and capability will automatically fall by the wayside in a competitive scenario. Amongst the private sector contenders, Larsen and Toubro, the country’s leading engineering conglomerate in the defence sector believes that it is eminently qualified to become the SP given its association with India’s indigenous ballistic missile submarine programme. Hindustan Shipyard Ltd Visakhapatnam, a DPSU located in Visakhapatnam is the only other shipyard with any submarine experience as it has undertaken medium repairs of the old Foxtrot class submarines and also the current Kilo class but then submarine repair is very different from submarine construction. The common thread amongst the other contenders is their total lack of submarine building or submarine repair experience with some of them not even having any experience of warship construction.

In the hope of generating competition, the MoD has actually made the selection process extremely complex. Each of the potential SPs who will get shortlisted based on their abilities will have to decide on the OEMs they wish to invite bids from. After this they will have to initiate detailed discussions with these OEMs on transfer of technology, design details, investment required for creating the required infrastructure, training of shipyard personnel, the workshare between the OEM and the SP, the actual build process, the level of indigenisation required and numerous other issues. Based on the bids they receive, they will then have to choose their partner and submit a bid. The SP’s interest will lie in winning the bid with maximum profit so it will most likely choose the lowest offer which meets the mandated requirements to increase its chances of becoming the L1.

This however may run contrary to the Government’s stated aim and expectation of getting significant value addition and deep transfer of technology to enable indigenous design and development of future submarine programmes. Transfer of Intellectual Property and meaningful ToT does not come cheap so the Government/Navy may have to re-define L1 with a weighted matrix to balance its requirement with the SP’s commercial interests and find an optimal solution which in itself will not be without its own problems.

From the OEM’s perspective, bidding for this programme is also a major challenge. For the last 10 years, these OEMs (incidentally 10 years ago too the submarine designs on offer were the same as they are now) have made innumerable trips to India to discuss the Indian requirements and have allocated resources to address these with little actual progress in the programme. Now they are in a situation where they have to respond to RfPs from one or more shortlisted SPs since the SPs are not keen on an exclusive arrangement with any one OEM at the RfP stage. Hence the OEMs presently have to engage with almost all potential SPs since there is little clarity on the shortlist as yet. Even after the shortlist, if there is more than one, the OEM cannot prepare a standard bid for all. It will have to individually engage with each one separately and develop a bid based on the capability, infrastructure, skill sets, track record, experience, risk etc of that particular SP. This in effect will require the OEMs to allocate internal resources as if they were simultaneously engaging with many customers. This will be a daunting task for the OEM and would definitely add to the cost of the programme.

There is also the very real risk that some of the OEMs may offer unproven systems still under development on the assumption that these would be operational by the time the programme requires them. However, if they fail to deliver by then, it will be too late to change.

Transfer of Technology.

The genesis of the 30 year Plan for indigenous submarine construction lay, as the very name suggests, in developing the capability for indigenous submarine construction. The Project 75 and Project 75(I) programmes were intended for India to collaborate with foreign OEMs for the construction of six submarines in each programme and thereby develop the capability to design and build our own submarines thereafter. However, even after 14 years of collaboration between MDL and Naval Group and the ongoing construction of six submarines, India is not very much closer to designing and building its own submarines than it was then. Hence it is important that Project 75(I) addresses this issue if we are indeed to become a credible submarine building navy. This will require further strengthening of the existing industry capability for absorbing submarine related niche technologies and providing an enabling environment with adequate volumes for favourable economies of scale. It has to be seen if the MoD/Navy/SP combine will be equal to the task.

Making the Best Choice.

India’s undersea warfare capability is passing through difficult times with ageing submarines. The new inductions have flattered to deceive with time delays, cost overruns and quality issues. The refurbishment of six of the older submarines to tide over this crisis is at best an interim arrangement. Given the present status of Project 75(I), it will be almost a decade, if not more, for the first submarine of this class to be delivered. It is therefore imperative that the options in Project 75(I) are carefully weighed, past experiences duly considered, risk mitigated by trusting proven technology and enabling a conducive environment for all stakeholders to expeditiously progress this programme towards delivering on its fundamental objectives of addressing the delays in submarine acquisition and making India a credible submarine building nation.

(Commodore Anil Jai Singh is a veteran submariner and the Vice President of the Indian Maritime Foundation. He is keenly interested in matters maritime and speaks and writes on the subject in India and abroad. The views expressed are open source and personal. He can be contacted on ajaisingh59@gmail.com )