- Aspires to be among ‘the greenest airports’ in Europe

London Oxford Airport is looking forward to breaking ground on its all new, self-funded R&D Science Park in January 2024. This follows the successful planning application of the £48 million development, which was approved last summer. Demolition of the original buildings has already started, paving the way for the new 200,000 sq.ft. facility, which the airport hopes will appeal to next-gen aviation and technology businesses, along with other spin-outs and start-ups from the University community. Building work will complete in time to see the first companies move in during Q4, 2024. Units will be available to lease via commercial property company Savills.

London Oxford Airport is looking forward to breaking ground on its all new, self-funded R&D Science Park in January 2024. This follows the successful planning application of the £48 million development, which was approved last summer. Demolition of the original buildings has already started, paving the way for the new 200,000 sq.ft. facility, which the airport hopes will appeal to next-gen aviation and technology businesses, along with other spin-outs and start-ups from the University community. Building work will complete in time to see the first companies move in during Q4, 2024. Units will be available to lease via commercial property company Savills.

In line with the airport’s desire to achieve sustainable growth, London Oxford Airport issued a fuel supplier RFP recently, while construction of a new fuel farm, which will eventually support five tanks and 425,000 litres of fuel, was completed in 2021. It has also confirmed plans to offer sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) in 2024.

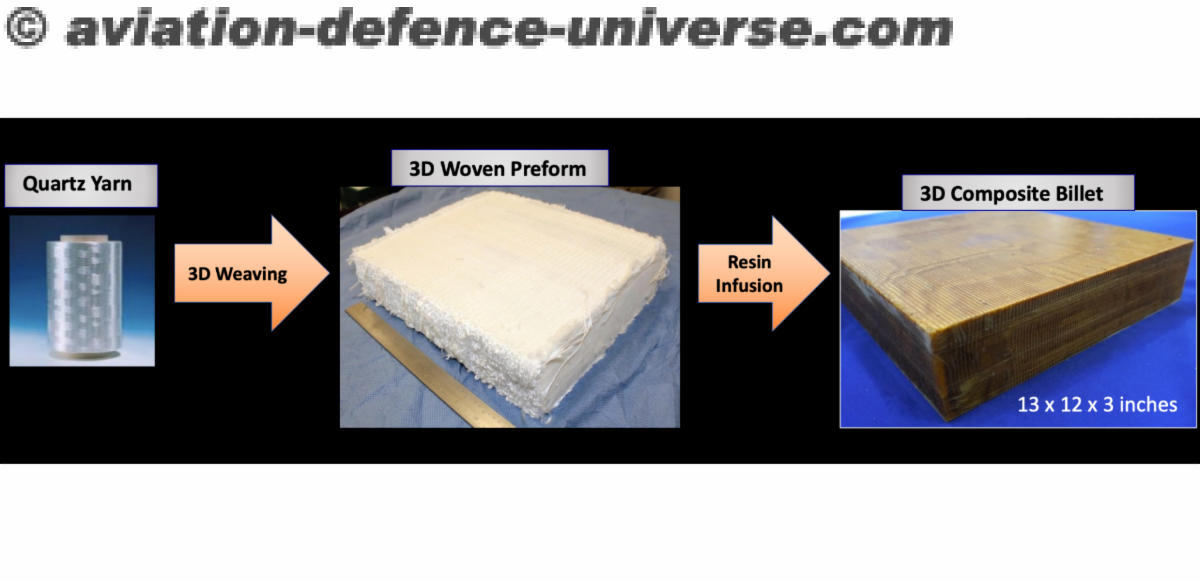

One of its new airport tenants is OXCCU, a spin out from the University of Oxford’s Chemistry Department. OXCUU is developing a drop-in synthetic aviation fuel, OXEFUELTM by taking atmospheric carbon dioxide and combining it with hydrogen. Using its bespoke and unique catalysts and reactors, OXCCU plans to turn H2 and CO2 into long chain hydrocarbons in one simple step.

Naomi Wise, OXCCU’s Interim Finance Director, speaking at the airport’s recent Disruptors’ Day, explained that others take carbon dioxide, turn it into synthetic gas, and then they make long chain hydrocarbons. “Doing it in one step we can recycle any of the unconverted gases back into the loop to improve our efficiency,” she said.

Airbus Helicopters to mark 50 years in the UK with new sustainable home

Meanwhile, work has started on Oxford Airport’s largest tenant, Airbus Helicopters’ new 125,000 sq. ft facility. Featuring provision for photovoltaic (PV) power, the site, which comprises 66,000sq ft. hangarage, 59,000 sq. ft. office space and workshops, along with seven helipads, is expected to be complete by summer 2024, coinciding with Airbus Helicopters’ 50-year anniversary in the UK.

For several years, one corner of the airport has been earmarked by Oxford County Council, firstly as a ‘Park & Ride’, but more recently as an integrated ‘Transport Hub.‘

Subject to approvals and with a nominal budget of over £20 million, this could see the combination of a Rapid Transit bus system, EV charging at large scale, e-bike hire and other ground mobility solutions, all coming together in one place. The airport sees this as an opportunity to explore further integration of that ‘hub’ with the provision of future air mobility offerings, however they may evolve – Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) – fixed wing air transportation and Urban Air Mobility (UAM), typically utilising electric vertical take-off and landing (eVTOL) vehicles.

Regional Air Mobility will be bigger than UAM – Darrell Swanson

UAM will be big in the future, but regional air mobility will be even bigger, highlighted Darrell Swanson, Founder of EAMaven. Noting that traditional mobility has “reached its limits,” the UK airport consultancy has identified 390 potential routes among 32 regional and business airports in the UK. It outlined one specific [albeit undeclared] route from London Oxford Airport which could generate £14.9 million in revenue annually. “To service demand using a nine-seater aircraft, supporting 82.5% load factor with 183,000 passengers per annum, we would need eight aircraft serving 3,600 hours of operations per annum. That’s high for a traditional turboprop, but with electric aircraft we’d be able to achieve those operational hours,” said Swanson.

UAM will be big in the future, but regional air mobility will be even bigger, highlighted Darrell Swanson, Founder of EAMaven. Noting that traditional mobility has “reached its limits,” the UK airport consultancy has identified 390 potential routes among 32 regional and business airports in the UK. It outlined one specific [albeit undeclared] route from London Oxford Airport which could generate £14.9 million in revenue annually. “To service demand using a nine-seater aircraft, supporting 82.5% load factor with 183,000 passengers per annum, we would need eight aircraft serving 3,600 hours of operations per annum. That’s high for a traditional turboprop, but with electric aircraft we’d be able to achieve those operational hours,” said Swanson.

He also underlined that “electric aviation (with the likes of upcoming programs like Eviation Alice, Heart Aerospace and Electra.Aero) will usher in significantly lower maintenance costs. “

The value of smaller airfields

The first movers to make a success in regional air mobility will be those who can call on a network of pre-existing licensed and unlicensed GA aerodromes (which would need to be licensed), suggested James Dillon-Godfray. They offer ‘ready-made solutions’ to the pressing challenges facing next-gen aviation.

They are “valuable assets and we need to protect our airfields, adapt and evolve them for the upcoming advanced and urban air mobility models.” Airports too will need to step up and invest in the infrastructure to handle electric aircraft. This, suggested Dillon-Godfray, can be anything from a 400kVA to 600kVA supply, up to a megawatt of power, simply to enable the fast charge of just one electric aircraft at any one time.

The solutions are not so straightforward, he proffered. When Oxford Airport needed to install a substation to power its new hangars, it took two years for the local power distribution network to deliver just 500kVA in power from its nearby grid connection.

Beyond that, thick copper cable needs to be installed underground from an associated substation to an airport charge point location. This infrastructure can typically cost £1,400 a metre, which could easily be something close to £500,000 for just a 350m run. Another challenge is the lack of commonality for EV charging points and specifications to power electric aircraft. “Aviation ideally needs to agree on one single system.”

Norwich-based SaxonAir, also participating in Disruptors’, hoped to showcase the UK’s first certificated electric aircraft – the Pipistrel Velis. There are 10 in the UK, one of which is based with SaxonAir at Norwich Airport. Lack of recharging stops en route, however rendered the flight unfeasible.

“We couldn’t do the trip from Norwich to Oxford because of the range gaps in the airfields,” said Alex Durand, SaxonAir’s CEO. “Some of the airfields we were looking to also wanted a risk assessment. This just served to show – the network isn’t ready.”

SaxonAir took on a year’s lease of the Velis to gain some experience.

“There is no regulatory framework, no maintenance framework, no training framework,” continued Durand. “We are just pretending it’s a helicopter or business jet in our fleet and we talk with the regulator in the same way.”

It will be even harder for hydrogen, he noted, remarking: “Electricity is at least available now. You can advance flying training with it. We have learned that people who are interested in flying, but haven’t learned, will, on principle, fly an electric trainer aircraft.”