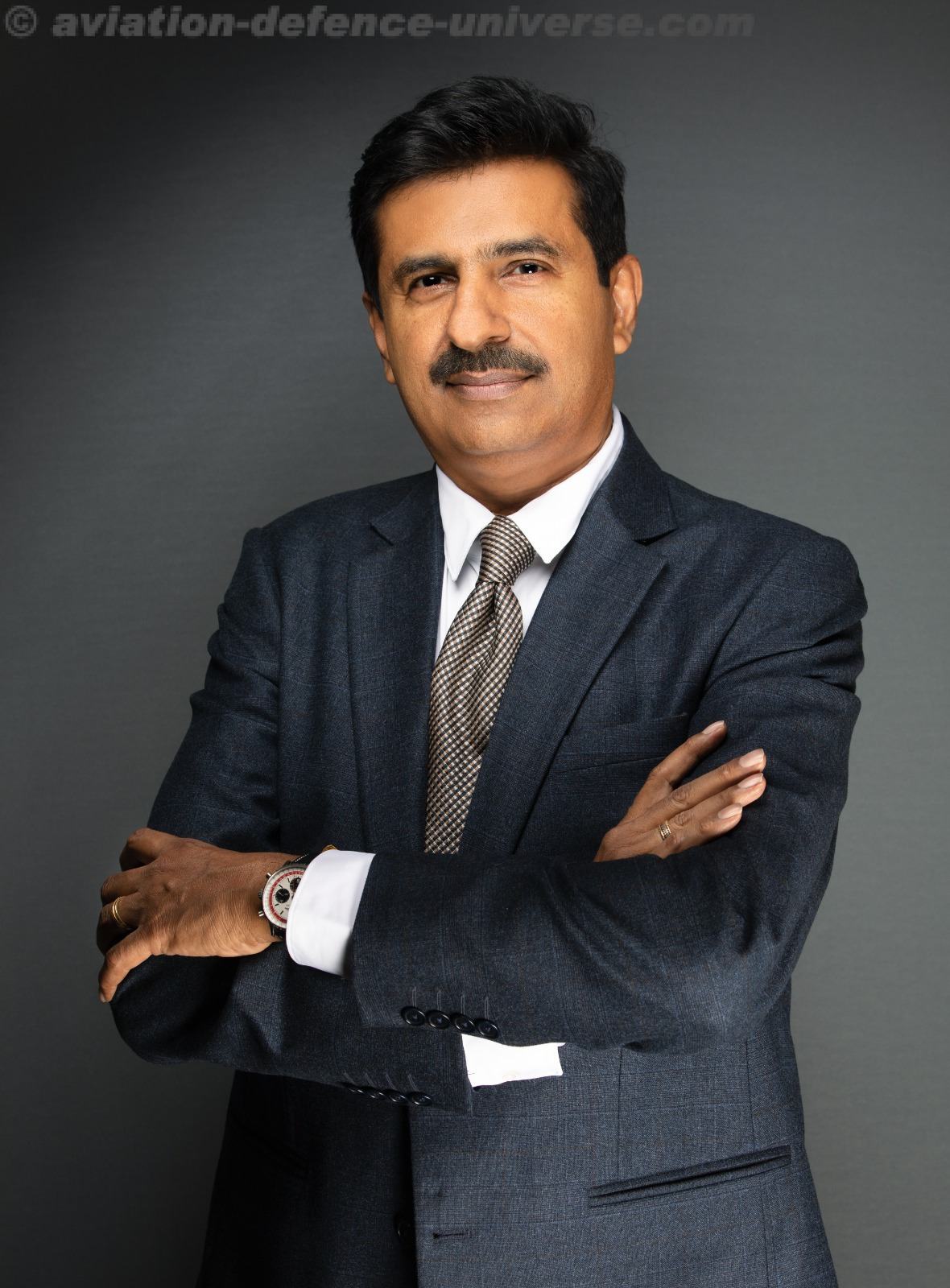

By Commodore Anil jai Singh, IN (Retd)

Vice President, Indian Maritime Foundation

New Delhi. 13 August 2024. As India celebrates its hard won independence on 15 August, one is reminded of Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru’s inspirational words in Parliament on this momentous occasion 77 years ago of India awakening to fulfil its tryst with destiny. Today, India stands on the cusp of a transformation towards fulfilling that destiny; a destiny that is inextricably linked to the maritime domain.

New Delhi. 13 August 2024. As India celebrates its hard won independence on 15 August, one is reminded of Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru’s inspirational words in Parliament on this momentous occasion 77 years ago of India awakening to fulfil its tryst with destiny. Today, India stands on the cusp of a transformation towards fulfilling that destiny; a destiny that is inextricably linked to the maritime domain.

India has emerged as the fastest growing large economy in the world. As it transitions towards a US$ 5 trillion economy in the next couple of years, a US$ 10 trillion economy within a decade from now and aspires to become a developed nation by 2047, India’s maritime capacity and capability will not only be a major factor in achieving that goal, but equally significantly, will shape the future geopolitical and the geo-economic contours of this region.

India is the undisputed pre-eminent power in the Indian Ocean region. The Indian Navy, which is the principal instrument of the country’s maritime power is on an impressive growth trajectory, and has firmly established the country’s credentials as a preferred security provider and a first responder in times of crisis. Its expanding footprint and the unprecedented operational tempo it has maintained in recent years is testimony to its professionalism and commitment to excellence. Its recent actions to protect global shipping transiting through the Bab-el-Mandeb Straits and the Arabian Sea during the recent Houthi attacks on merchant shipping and the resurgence of Somali piracy, won it wholesome global praise. The diversion of shipping around the Cape of Good Hope to avoid the Houthi attacks with their increasingly impressive array of weaponry was already causing ripples in the shipping world. While India wisely decided not to involve itself in the Red Sea fracas, its pro-active counter-piracy actions ensured that this disruption was not repeated in the Indian Ocean, and prevented a major global economic setback. At one point in time, 12 Indian Naval ships were deployed in the western Indian Ocean to counter the piracy threat.

India is the undisputed pre-eminent power in the Indian Ocean region. The Indian Navy, which is the principal instrument of the country’s maritime power is on an impressive growth trajectory, and has firmly established the country’s credentials as a preferred security provider and a first responder in times of crisis. Its expanding footprint and the unprecedented operational tempo it has maintained in recent years is testimony to its professionalism and commitment to excellence. Its recent actions to protect global shipping transiting through the Bab-el-Mandeb Straits and the Arabian Sea during the recent Houthi attacks on merchant shipping and the resurgence of Somali piracy, won it wholesome global praise. The diversion of shipping around the Cape of Good Hope to avoid the Houthi attacks with their increasingly impressive array of weaponry was already causing ripples in the shipping world. While India wisely decided not to involve itself in the Red Sea fracas, its pro-active counter-piracy actions ensured that this disruption was not repeated in the Indian Ocean, and prevented a major global economic setback. At one point in time, 12 Indian Naval ships were deployed in the western Indian Ocean to counter the piracy threat.

The nature of the maritime threat has evolved beyond the traditional state on state conflict and now includes a wide spectrum of non-traditional and transnational maritime security challenges. Thess include maritime terrorism, piracy, arms and narcotics smuggling, human trafficking, and Illegal Unregulated and Unreported (IUU) Fishing, amongst many others. The effects of climate change and global warming has added a new dimension with Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR) becoming increasingly important. Hence, even though the primary role and raison d’etre of the Indian Navy remains warfighting and defending the territorial integrity of the nation, it has had to adapt its strategy, force structuring and deployment pattern to this evolving maritime security paradigm. An often less understood fact about the role of navies is that unlike the army and the air force whose deployment is clearly defined by distinct land borders and inviolate air space (even if these are disputed), the country’s maritime frontiers extend across the oceans to protect India’s national interests ‘anywhere, anytime and anyhow’ ( as articulated by the present Chief of the Naval Staff on taking over the helm of the Indian Navy in May 2024). In India’s case they extend from defending India’s strategic and economic interests from the eastern shores of Russia in the east to the western shores of Latin America in the west. Keeping the slew of maritime challenges at bay in the wide expanse of the region is a 24/7 activity akin to keeping a vigil on our borders and our sovereign airspace.

India is essentially a maritime nation. It has been blessed with a very favourable maritime geography. Its pivotal position, with its peninsular tip jutting almost 1000 miles into the central Indian Ocean enables it to straddle some of the world’s most strategic and critical international sea lanes. The southern tip of the Andaman and Nicobar islands on India’s eastern seaboard are strategically located at the western approach to the Malacca Straits, which is arguably the most important choke point for international trade. Similarly important sea lanes passing south of the Lakshadweep archipelago on India’s western seaboard offer a strategic advantage. However, India’s maritime location while being a strength is also a vulnerability, as more than 90% of Indian trade by volume and over 74% by value travels over the sea. 80% of India’s oil and gas transits across the oceans from different parts of the world. Even the major share of our domestic production is offshore. Hence, ensuring the safety of our trade and the security of our energy is critical for the economic well-being and the security of the nation. As India grows economically during the next 25 years of Amrit Kaal, its overseas trade and energy requirements will also grow exponentially, as will the challenge of ensuring its safety.

India is essentially a maritime nation. It has been blessed with a very favourable maritime geography. Its pivotal position, with its peninsular tip jutting almost 1000 miles into the central Indian Ocean enables it to straddle some of the world’s most strategic and critical international sea lanes. The southern tip of the Andaman and Nicobar islands on India’s eastern seaboard are strategically located at the western approach to the Malacca Straits, which is arguably the most important choke point for international trade. Similarly important sea lanes passing south of the Lakshadweep archipelago on India’s western seaboard offer a strategic advantage. However, India’s maritime location while being a strength is also a vulnerability, as more than 90% of Indian trade by volume and over 74% by value travels over the sea. 80% of India’s oil and gas transits across the oceans from different parts of the world. Even the major share of our domestic production is offshore. Hence, ensuring the safety of our trade and the security of our energy is critical for the economic well-being and the security of the nation. As India grows economically during the next 25 years of Amrit Kaal, its overseas trade and energy requirements will also grow exponentially, as will the challenge of ensuring its safety.

India’s 7516 km coastline runs along nine states and four union territories with more than 200 million people dependent on the sea for their livelihood and existence. India’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), which extends 200 nautical miles into the sea covers an ocean area of over 2.03 million sq. kms which is rich in natural resources. As land resources become increasingly scarce, it is this EEZ, that the country will turn towards to ensure its development goals and the sustenance of its people. Therefore, not only is the Indian Navy responsible for protecting India’s global interests, but also has to ensure that it retains the maritime edge in its strategic maritime neighbourhood.

The recent political developments in India’s vicinity be it Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Maldives, Pakistan or the recent political upheaval in Bangladesh are a matter of concern as these could directly impact the prevailing security dynamics in the region. The Bay of Bengal is of particular concern and these events could impact the existing status quo; India could find its predominance in these waters being challenged by extra-regional navies seeking a foothold in these waters. China, which has already made inroads into the Bay of Bengal with its presence in Sri Lanka, its military engagement with the military junta and the development of the Kyaukphu port in Myanmar, and the construction of a submarine base in Bangladesh ostensibly for the Bangladesh Navy (ironically named BNS Sheikh Hasina), will soon have a permanent naval presence in the Bay of Bengal. If the US is also seeking a foothold in the Bay of Bengal as media reports would have us believe, and if the ‘white man’ ( to quote Sheikh Hasina) could go to the extent of effecting a regime change in Bangladesh for establishing its presence, then the Bay of Bengal is going to become embroiled in the emerging Great Power contestation in the Indian Ocean region. If this were to happen, it would also impact India’s position of strength in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, while mitigating Chinese concerns about its Malacca Dilemma. This is not a comforting thought for India which will have to develop adequate capacity and capability to ensure that its favourable maritime position in the Indian Ocean is not compromised.

In the last decade or so, the government has laid considerable emphasis on developing India’s maritime capability. Here it is important to highlight the distinction between a country’s naval power and maritime power. While India is a formidable naval power in the Indo-Pacific, it is far from being a maritime power. It has a miniscule share of the global shipbuilding market ( less than 0.5%), its ship repair and ship recycling industries need urgent modernisation in keeping with global environmental standards, its merchant fleet is antiquated and depleting in numbers, its fishing community still relies on inefficient and suboptimal traditional fishing practices, and the modernisation and augmentation of its port infrastructure is still a work in progress. The government has put in place programmes like Sagarmala to address these deficiencies but these need to be fast tracked with committed funding and an enabling policy environment to ensure timely implementation in accordance with India’s Maritime Vision 2030.

The Indian Navy’s impressive track record should not lull the powers-that-be into a false sense of complacency. There are some glaring gaps in the navy’s force structures which need urgent attention. Ship building is a time consuming and capital-intensive activity which needs advance planning, committed long term funding and timely implementation to ensure the desired level of readiness in a defined time frame. India’s security concerns in the region have been repeatedly flagged by successive Chiefs of the Indian Navy at various fora but the decision making in the hallowed portals of South Block continues to proceed at its own pace. Critical programmes like the third aircraft carrier, the long outstanding proposal for a nuclear attack submarine (SSN) fleet, the delays in the 30 year conventional submarine building plan, the lack of adequate minesweeping capability , the deficiency in the navy’s rotary wing ( helicopters) numbers etc, are vulnerabilities that need to be addressed at the highest levels.

India has been the world’s largest importer of military hardware for many years. This dependence on imports is a critical vulnerability for a country of India’s size and influence, and has led to a concerted effort towards ensuring indigenisation and self-reliance in the defence sector. However, the indigenous R&D effort is often marred by ambitious timelines, misleading assurances and long delays in developing the desired capability and leads to the capability deficits widening over time.

India has been the world’s largest importer of military hardware for many years. This dependence on imports is a critical vulnerability for a country of India’s size and influence, and has led to a concerted effort towards ensuring indigenisation and self-reliance in the defence sector. However, the indigenous R&D effort is often marred by ambitious timelines, misleading assurances and long delays in developing the desired capability and leads to the capability deficits widening over time.

India @ 77 aspires to be a major regional power in an emerging multipolar world. While it must celebrate its continuing upward growth trajectory, it must also reflect on addressing the existing and emerging maritime security challenges that could adversely affect this growth story. It is essentially a maritime nation with its future firmly anchored in the maritime domain. It has established impeccable credentials as a leading Indian Ocean power and takes the responsibility of being a force for good very seriously. With the Indian Ocean region going to figure prominently in the emerging great power contestation within the next decade, India has to ensure that it develops the necessary maritime capacities and capabilities within this period to shape the outcomes in this region, and not allow itself to be shaped by them.