Speaker: Bob Stone, Director, Human Interface Technologies Team, Department of Electronic, Electrical & Systems Engineering – University of Birmingham

Session: Medical Innovation: Mixed Reality Technologies for MERT Training – Project Achievements and Lessons Learned

Q. Can you give an overview of your background and how you became involved in DSEI 2019?

A. I’ve been involved in the international virtual, augmented and mixed reality community world for over 32 years, and my background is in human factors, which involves making sure the technologies we deliver to the Armed Forces are fit for purpose for the range of future training tasks personnel may be required to undertake.

Today I work closely with the Royal Centre for Defence Medicine and various UK hospitals, researching the use of virtual reality (VR) and mixed reality (MR) for physical and mental health restoration and rehabilitation, and for the training of future Medical Emergency Response Teams (MERTs).

Q. What is the focus of your visit to DSEI?

A. My team has been working on a contract with the Royal Centre for Defence Medicine for the past three years and September marks the end of that project, so it is a big moment for us.

The project we have been working on is the MERT Mixed Reality Project. Within the world of the UK’s Defence Medical Service’s Pre-Hospital Emergency Care capability, MERTs are teams of personnel that possess a wide range of medical skills, including emergency medicine-qualified nursing officers and paramedics. The principle goal of these teams is to enhance the survival outcomes for major trauma casualties whilst en route from the point of extraction to a more centralised and comprehensively equipped hospital facility.

Currently MERTs train using role-play within CH-47 Chinook rear cabin mock-ups. However there are only two of these available in the UK, so access to them is limited and their running costs are very high. They also cannot be reconfigured to represent other UK armed force transport assets.

We have spent a lot of time working with the Royal Air Force, Royal Marines and British Army, looking at how an MR training concept demonstrator could support future training requirements with a solution that helps overcome many of these restrictions.

Q. What exactly is the demonstrator and what is it designed to do?

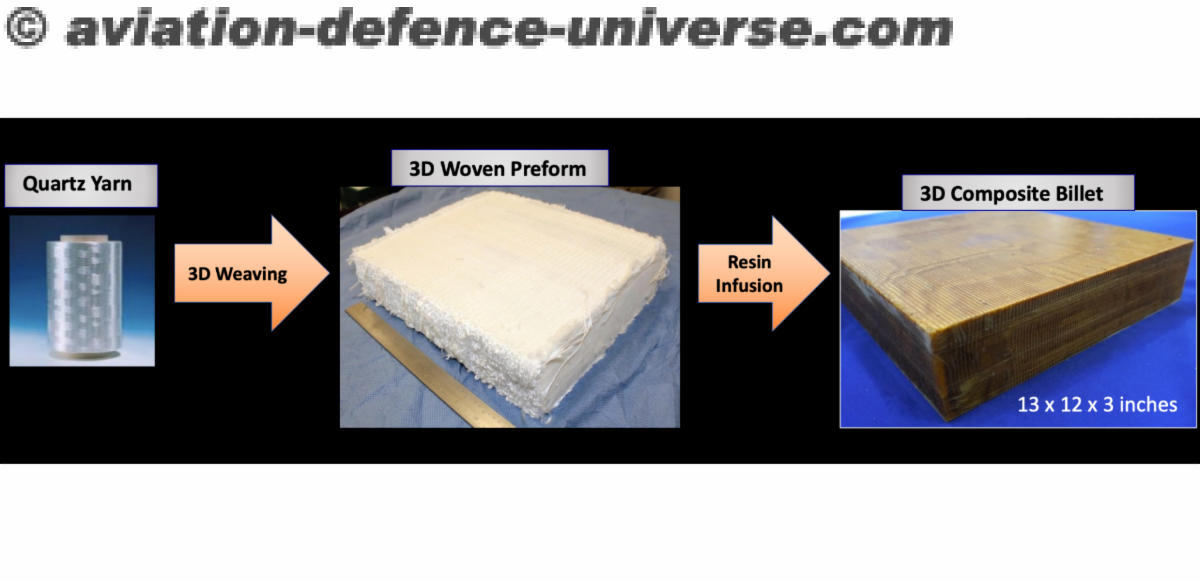

A. The system began as a demonstrator based on a rapidly inflatable enclosure, various physical items – “space fillers” – and a realistic human mannequin featuring interchangeable limbs and a variety of simulated wounds. Trainees wore VR head-mounted displays to experience being ‘present’ within a Chinook helicopter in flight, including sounds and 2D virtual screens located outside the VR cabin, onto which in-flight images, captured using one of our drones, were projected.

VR alone proved to be incapable of providing a realistic training environment, however, so an augmented reality (AR) version of the VR head-mounted displays in use was developed, by using a ‘pass-through’ camera attached to the front of the display unit. This enables visual aspects of the real world to be seen in addition to those of the virtual world.

This allows the trainee to see their own hands and the real mannequin, as well as a virtual construction of the aircraft cabin that can be reconfigured to meet different platform types.

Q. What makes the trainer unique?

A. Because we were able to work so closely with the end user, we were able to cut through the hype associated with virtual and augmented reality training, which is all too evident these days in online newsletters and press announcements. Despite the illusion created by these features that VR and AR systems can do everything, in reality they cannot. So what we’ve done here is to define those parts of the training system that need to be ‘real’ and those that can be generated virtually, in order to deliver a system that is fit for purpose.

The result is that we have a very realistic looking human casualty mannequin on a real stretcher; we have real medical equipment; and by wearing the modified VR headsets, trainees undergo training inside an enclosure in which all surfaces consist of blue material. So, using similar Chroma Key techniques to those used in movies and TV productions, when they look up they are inside a military platform – and when they look down they see the real mannequin, stretcher, and more importantly their real hands touching the mannequin and medical kit – something current-generation “haptic” (force and touch) wearable technologies simply cannot deliver.

Q. What is next for the project?

A. We are going to be engaging with other potential users – specifically the Royal Navy, Royal Marines, and more with the tactical medical wing at RAF Brize Norton – to develop a number of scenarios and new virtual reality scenes that will future-proof the system. The plan then is to work with a small company who will be exhibiting with us at DSEI – MODUX Ltd – to then ‘productise’ the MERT trainer and take it to market.

Q. What are some of the challenges that remain in this sector?

A. Users are very accepting of the fact that training technology is heading down the VR route. What we’re still teaching people to do, however, is avoid the hype. There’s still a lot of money being wasted by people buying things such as headsets, be they VR or AR, believing that this tech will instantly solve their training problems. So one of my big messages will be ‘don’t believe everything you see or read online’.

The other big challenge is getting real human performance data of the kit being used. Often too little time is being spent on actually doing experiments with the end users, with the technology, and seeing how that helps them transfer their skills and knowledge from the virtual to the real. It’s sadly lacking, and needs to change very quickly, because even though we have acceptance that the tech has amazing potential, people are still asking: prove it; what’s the ROI? How do I know that this kind of training actually delivers value for my trainees? And unfortunately there isn’t enough out to answer these questions with confidence there right now. We’ve done our bit in the last 20 years in terms of doing experiments as best we can, but it’s still pretty thin on the ground. So the evidence based research and evidence based trials is still the big challenge for this technology.

Q. What are you most looking forward to at DSEI?

A. Engagement with the customer. We’re keen to show what the technology is doing to all ranks and at all levels both within the armed forces and governmental – as well as on the international side.